Blog / 2013 / Why I Can Write a Book about Science Even Though I’m Not a Scientist

May 22, 2013

My credibility as the author of Crime Against Nature, a book about science, has been called into question now and again, most recently here. According to those who challenge me, the reasons to doubt me are:

- I’m not a scientist.

- I’m not affiliated with an academic institution.

- I didn’t provide a full bibliography for my book.

Though it irks me to have my integrity questioned, I get where these concerns come from, so I’m going to answer them here.

In response to #1

I’m glad I’m not a scientist. If you think it’s hard to find funding for an art project, check out the chapter in Michael Stebbins’ Sex, Drugs, and DNA about the scientist’s life. It’s a wonder there’s any innovation or honesty in scientific research in the US with all the competition and bureaucracy surrounding grants, publishing, and seemingly all aspects of a scientist’s career.

In response to #2

I have a hard time seeing how anyone would find me more credible if I had an MFA, but, if this sort of thing really matters to you, I graduated from Willamette University summa cum laude with a BA in studio art, art history, and French while also earning membership in Phi Beta Kappa, an academic honor society.

Of course, I did all that ten years ago, and in the meantime I’ve been independent, without institutional oversight or backing for anything I’ve done, unless you count the numerous grants I’ve received and the multitude of venues in which I’ve shown. That I’ve spent that decade making my living as an artist with the help of individuals who pay me for my work with their hard-earned cash probably means nothing to someone who cares only for academic accolades, but it means the world to me.

In response to #3

I regret not keeping better notes about my sources as I did my research. Part way through the project, I started to, but, in the end, with only half a paper trail, I opted for a “further reading” page at the end of my book instead of a full bibliography.

And I feel good about that choice because almost none of the information presented in the book is questioned by the scientific community. The majority of it is readily available from a variety of sources. In other words, the fact that a female komodo dragon can make male babies without the help of a mate, that plenty of females are larger than the males of a species (like with this one, this one, and this one), and that Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer is a girl is not surprising to anyone who knows anything about biology.

What’s new about Crime Against Nature is the presentation. I am juxtaposing simple scientific facts with each other to help prove a social fact that we don’t like to admit: that we—scientists and laypeople alike—are more influenced by traditional notions of gender than we realize.

And though the narrative arc of my book is entirely my own and a number of my animal examples come from combing through the life cycles of umpteen species, I’m not pretending I did this all on my own. I was originally inspired to look at nature in this way by Joan Roughgarden first and then by Bruce Bagemihl, both of whom also provided many of the animal examples I use and both of whom I cite in my “further reading” section. And Dr. Roughgarden felt good enough about Crime Against Nature to provide the foreword for it.

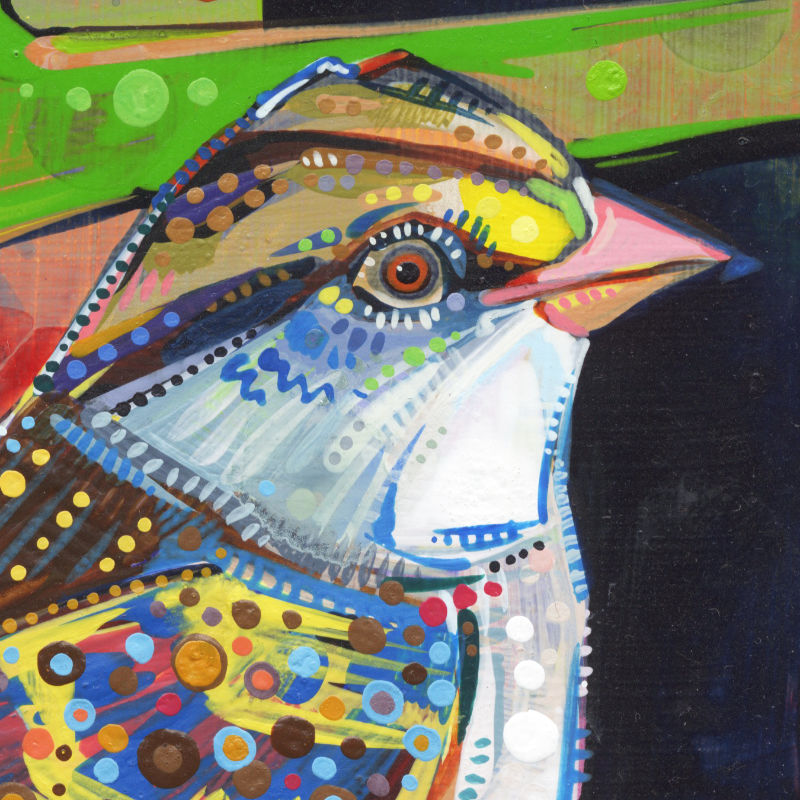

As I said, it’s easy to track down most of the facts I presented in my book, but I did have a little trouble with the creature depicted in the above painting process video. White-throated sparrows come in four genders, distinguished by their sex and their behaviors as well as by their appearance. Some females have white stripes above their eyes, while others have tan stripes; the same goes for males. The colors of the stripes correlate with behavioral tendencies in both sexes, and the optimal pairings for these sparrows seems to be a female-male team with one tan-striped bird and one white-striped bird.

Mr. and Mrs. Right, Mr. and Mrs. Also-right (White-throated Sparrow)

2012

acrylic on panel

10 x 10 inches

As a layperson, I had to do a bit of detective work to be sure I was painting these birds correctly. I couldn’t just visit an academic library with all its research goodies. I had to contact a birding society and ask members if there was a size difference between females and males in this species.

I was told “no” and that the only way to tell the difference between the sexes from a distance was by observing behavior. The “no” was useful, but the rest of the answer was telling. Because that’s the point of including white-throated sparrow in this series: no matter the sex, white-striped birds are more aggressive and territorial, while tan-striped birds are less so.

This lack of knowledge didn’t surprise me. A brief visit to a fishing forum online will reveal that many who enjoy the sport don’t realize that jack salmon aren’t confused juveniles but full-grown males with a special ecological niche to fill.

The other animal that gave me some trouble is the one depicted in this painting process video. Mandrills remain something of a mystery. We know that males are more colorful than females, that the males’ facial markings are more intense, and that they’re the ones walking around with the equivalent of a neon sign on their rumps.

What’s less understood is why the males have these technicolor dream butts. There’s an idea that, since the coloration is more pronounced in dominant adult males, it’s probably to help guide a male’s troop of females through dimly lit forests. But that idea isn’t totally accepted.

Males and their Technicolor Dream Rumps (Mandrill)

2012

acrylic on panel

10 x 10 inches

According Natalie Angier in “In Mandrill Society, Life Is a Girl Thing,” an article originally published in The New York Times and reproduced in The Best American Science Writing 2001, males only spend time with females when they’re in estrus. Otherwise, the boys are off on their own—and I mean completely on their own, not in bachelor groups. What’s more the females live and travel in groups of 800 individuals foraging for food as they go, so I sort of doubt that one male is going to lead the group with or without the help of a colorful behind!

When it’s time to mate, males approach the females and compete for access, fighting violently and harming each other quite a bit. Though mandrills are often compared to baboons, this violence is different than that of baboon society. Among baboons, males maintain a harem and their violence tends to be directed at their females, but, among mandrills, females are rarely abused by males. In other words, there seems to be strength in the female bond, and the males’ neon butts are still a very pretty puzzle.

None of my research is earth-shattering or even particularly hard to find. And that means it doesn’t matter whether or not I have a BS: the point is that I am not full of it.

To those who still think I shouldn’t write a book about science, I have only this to say: you are narrow-minded and it’s your sort of separate-silos only-those-with-institutional-backing-can-speak-with-authority vision of the world that’s getting us into trouble. The knowledge that scientists discover won’t reach its full potential until someone with a real understanding of communication comes along and introduces it to a wider context.

Did this post make you think of something you want to share with me? I’d love to hear from you!

To receive an email every time I publish a new article or video, sign up for my special mailing list.