Blog / 2008 / Words, Words, Words...

May 13, 2008

The written word is the tyrannical little brother of images. It’s likely that written language developed from pictographs—the kind of notation used by ancient Egyptians or Sumerians, for example. These set-meaning images eventually became the various characters that all modern languages use. But even though the written word originated in images, it now has authority over the more flexible and imaginative kind of visual recording.

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but text associated with an image can also very easily turn the image into a mere illustration of those words.

The power of text comes directly from the dictionary. Because words have standardized definitions, they give the impression that they communicate ideas more faithfully, when, in reality, they’re as open to interpretation as images.

I used to feel betrayed by words. In school, I struggled through all my term papers. I wanted to use paint to synthesize my research, not words. Once in the real world, I resented having to write artist statements for my series. Even titling works was an agonizing experience.

Clearly, as evidenced by this blog, I’ve gotten over it! I’ve come out of the closet to myself: I’m a certifiable word nerd. That said, I still hesitate to put words directly into a composition. Their perceived authority has a way of dominating the immediate attention of the viewer and taking away from the rest of the painting. It seems like our brains can’t see a word without reading it. It’s as though we recognize letters as letters and, in the very next moment, we have read them.

Over Grown Up (Woman)

2006

acrylic on unmounted canvas

24 x 120 inches

I first experimented with embedding words in compositions in 2006, with my pieces for the group show inCLOVER—including the one shown above. The text embedded in those works was taken from Betty Crocker’s Hints for the Homemaker and from one of my partner’s original stories. You can read it all here and here.

During the show, I observed that people interacted with the pieces in an interesting way. I liked how the words drew viewers closer to the paintings, but I was distressed that their more intimate behavior was motivated by a need to read words instead of to enjoy brush strokes. I also appreciated how the words encouraged people to spend more time with the work, but, in the end, I felt like they were looking at the wrong thing. They were reading my work, and I wanted people to be looking at it. I didn’t include words in another composition again until this year with these three paintings from Apple Pie.

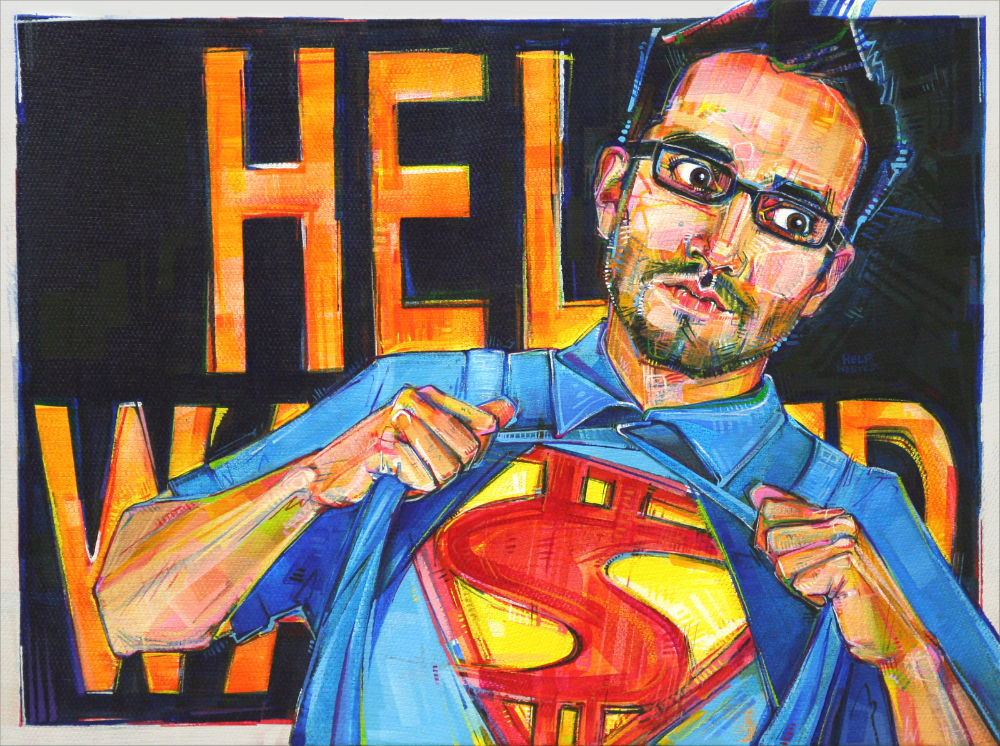

This Looks Like a Job for a Chicano! (Mexican-American, Luis)

2008

acrylic on bird’s eye piqué

19 x 25 inches

(For more information about the making of this painting, visit this post.)

I labored over the background of this painting for many months. At one point, Super Chicano was changing in a voting booth. Later, he was bursting out of a comic strip frame, crossing not-so-inviolable borders. Still, none of it conveyed what I wanted it to.

Eventually, I settled on the “help wanted” sign. I wasn’t thrilled by the idea of using words, but I felt like I could get away with it here. Those words in this format (with the recognizable coloring and partially obscured by the subject) read more as a symbol. Viewers seem to intuit what the words are more than read them. I am satisfied with that.

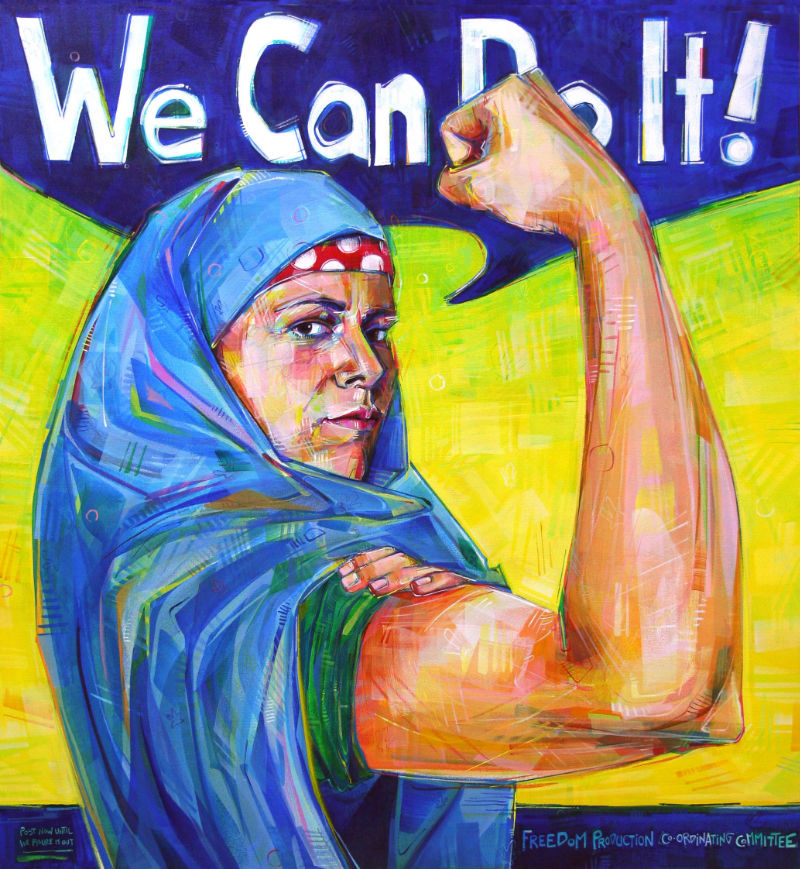

Raha the Riveter (German-Iranian-American, Kristina)

2008

acrylic on canvas

41 x 38 inches

(For more information about the making of this painting, visit this post.)

This painting and the following one are based on World War II propaganda posters. I didn’t feel like I could take the words out altogether, but I did consider carefully whether or not to change them.

With Raha The Riveter, I kept the big-lettered words exactly the same. The statement is so strong and so strongly associated with the image that I didn’t see a reason to alter it. With my painting, I intend to give a new face to the “we” in “we can do it,” to reveal the diversity of Americans who are part of that “we” today. Of course, viewers don’t always understand the words that way when juxtaposed with Raha instead of Rosie! And I’m glad for the variety of interpretations. The space between how I understand the image/word combination and how others do is where important conversations happen.

Chú Xam (Vietnamese-American, Nam)

2008

acrylic on canvas and eyelet

36 x 24 inches

The original Uncle Sam poster reads “I want you for US Army.” I considered changing the phrase to “I want you for US citizen,” because I liked the double meaning there. It could translate to “I want you to really take on the role of citizen” or it could act as an invitation to people from other countries to immigrate to the United States.

“I want you to love my country” was a riff off of a suggestion from my father. I like the confident ownership of “my country,” and I’m drawn to the ambiguity that, as with Raha The Riveter, allows certain viewers to discover their biases. Why can’t a hyphenated-American (and specifically, one who is not white) mean the United States when he says “my country?”

Did this post make you think of something you want to share with me? I’d love to hear from you!

To receive an email every time I publish a new article or video, sign up for my special mailing list.